What is Human Factors Psychology?

Summary: If you’ve already read our article “What is Human Factors” you know human factors specialists apply knowledge of human psychology and physiology to improve system design. This article dives into more detail around how understanding human psychology lets you design systems that are easier for human beings to wrap their brains around!

By Greg Hallihan on May 19, 2021

Psychology Generally

Psychology in general is the study of human cognition and behaviour. Basically, psychologists study whatever is going on in your brain, and the relationships of antecedent and subsequent factors related to those goings on. The general goal in the discipline is to create a better understanding of how our brains help us successfully navigate the world around us and apply this understanding in some useful way. This is a big field of study with a host of subdivisions and specialities, like clinical psychology for folks interested distress or dysfunction or social psychology for those interested in the the influence of others. One of these subdivisions is Human Factors!

Human Factors Psychology

Human Factors psychology refers to the application of psychology in the design of better technologies, environments and processes. You might already be familiar with the field or term “ergonomics”, which is the application of knowledge regarding human physical and physiological limitations and capabilities to design. We intuitively understand and appreciate that ‘ergonomic’ office equipment has been designed to be comfortable for our bodies and easy for us to interact with physically. Human Factors psychology can be thought of as cognitive ergonomics, and the goal is to design things to be comfortable for our brains and easy for us to interact with cognitively.

If you’ve ever assembled your own furniture, you may have noticed that some company’s instructions are better than others. Good instructions make it clear what you’re supposed to do by aligning well with the task you are trying to accomplish and how you think about it. This is an example of Human Factors psychology, applying an understanding of how someone thinks about building furniture to the design of the accompanying instructions. This understanding of what is ‘comfortable’ for our brains comes from the field of psychology, researchers and scientists have produced incredible amounts of information regarding the way our brains work, from how the human visual system processes information to how cognitive biases affect decision making.

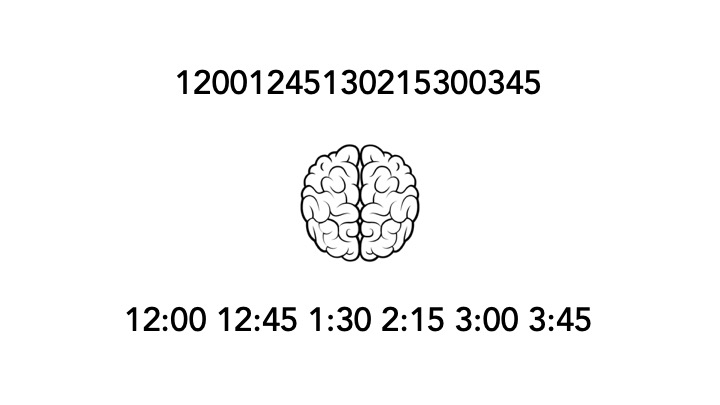

Take a look at the image below, there are two rows of numbers one on top and one on the bottom. Take 15 seconds to try and remember all of the numbers in the top row, then do the same thing with the bottom row. One set is easier than the other, even though the numbers and sequence are identical, this is because the numbers on the bottom have been ‘chunked’ in such a way that they’re easier for our brains to remember (as discrete times) and the format make an obvious pattern emerge (increments of 45 in a base 60 system).

This is a simple example of Human Factors psychology; examine a system like a string of numbers, consider the relevant limitations and capabilities of the human brain, and implement design solutions to make it easier for a human to successfully complete a task, like remembering the string.

What ‘Psychology’ is Relevant?

There’s a lot of knowledge about human psychology out there, so figuring out what and how to apply it can be challenge. Luckily, much of this knowledge has already been aggregated into design standards for common systems (e.g., Technical Basis for User Interface Design of Health IT). Becoming familiar with existing standards, and getting some experience interpreting and applying them across different projects simplifies the process.

In those instances were a standard doesn’t exist, you might need to do a a little more legwork and do some secondary research to define the psychological characteristics relevant to your system. Document what the human’s in your system are thinking, feeling and doing, then figure out how those human characteristics interact with the design of the system (remember the Human Factors ‘formula’).

Lastly, secondary research and design standards will help you inform the design of better systems, but if you actually want to test the performance, you’re going to need to do some research of your own. This could involve things like Time Motion studies or Usability Testing. Human Factors Research methods are the topic of another article, but the long and the short is you need to study people actually using the system in a realistic context to know how the system is performing.

Examples of Human Factors Psychology

Improving Satisfaction

There are a bunch of ways we can design more “satisfying” systems through human factors psychology. But one of them is by aligning the design of the system we are using with human expectations. These expectations often exist because we have learned them through life experiences and they reduce uncertainty in the world around us.

Imagine any situation in which you are waiting, whether it’s for a package to arrive in the mail or for customer support to pick up while you are on hold; we expect to know how long we will be waiting and that wait is immeasurably worse when we don’t know. The uncertainty and lack of control associated with an unknown wait time causes psychological discomfort.

The simple application of this knowledge is to make sure when we design a system that involves waiting, we provide individuals with a sense of how long that wait will be. Even though we aren’t reducing the wait time, the experience will be less psychologically stressful and ultimately more enjoyable. No matter how mesmerizing the spinning rainbow wheel is I’d prefer a process dialog.

Increasing Efficiency

Our brain is wired to process information in such a way that it creates inherent strengths and weaknesses; we’re pretty good at detecting patterns and categorizing things, but we aren’t great at quickly storing long strings of data in long-term memory. One of the things a Human Factors specialist tries to do is align the design of a system with how our brains are wired to make a system easier or more efficient to use.

Imagine the last time your IT admin asked you to change your password. The requirements might include things like using special characters, avoiding familiar phrases or personal connections, having a minimum length, or they might give you a randomly generated alphanumeric password. These requirements may make for great password security but they can be hard on our brains. Unfortunately, we have determined that the best way to design a password that’s hard for a machine to guess simultaneously makes it difficult for a human to remember.

Our brains are good at remembering and storing a limited number of ‘chunks‘ of information. A password like 7AvV14@b has 8 unique digits that don’t chunk well, each character and the order they are in has to be individually remembered. However, password like GiganticToastersCookGiganticToast! has 34 characters but chunks easily into 5 words, follows conventions for capitalizing the first letter of words in a title, and creates a visual image. The latter will be much easier to remember despite having many more characters.This XKCD comic does a great job articulating the value of a password system that focuses more on combining memorable chunks of information into longer strings.

By chunking the information we have to remember, we can lengthen a password simultaneously making it harder for a machine to guess. This approach leverages Human Factors Psychology by re-designing the password system to make it easier for humans to use without compromising performance (e.g., lost passwords or hacked accounts). Interestingly, dis-regarding the Human Factors psychology of passwords has unintended consequences. People are great at finding work arounds when they are forced to interact with a difficult system, and in the case of poor password design the result is all too often passwords written down on sticky-notes tucked under mousepads!

Enhancing Safety

Perhaps the most critical application of Human Factors psychology is in the realm of designing safer systems. When the brain processes information and an individual executes an action based on that processing, there will be a outcome that is either intended or unintended. Finding opportunities to reduce the likelihood that human actions lead to unintended, harmful outcomes is the bread and butter of a Human Factors specialist. This has been historically well documented in domains like healthcare and patient safety.

Try to remember the last time you were really tired driving, so tired you thought to yourself “maybe I shouldn’t be driving”. In that situation, you’re experiencing fatigue and your driving performance starts to suffer. Even though it’s an incredibly important task (i.e., piloting a speeding chunk of metal past other speeding chunks of metal) the fact that you’re fatigued impairs your driving ability; response times start to slow, you experience micro-sleeps and have trouble paying attention to the road, you catch yourself drifting across the lane now and again. You decide to pull over and get some rest or someone in the car takes over.

Now imagine you can’t just stop driving or get a friend to take over. What if you’re a fatigued nurse working in an ICU, or a roughneck working on an oil rig? It might be tricky to let your team or management know you’re feeling tired and your ability to keep yourself or others safe has been compromised by fatigue, especially if there’s an expectation for you to ‘tough it out’.

Failing to consider Human Factors psychology can have serious consequences when humans are interacting with systems that are ‘safety critical’. The role of a Human factors specialist is to improve system safety by designing systems that don’t force people to operate in unsafe conditions (e.g., helping define maximum shift lengths or minimum staffing levels to prevent fatigue) or design systems to be error tolerant (e.g., implementing the use of safety harnesses or procedural double checks on medication administration).